You click a link. It takes you to a site that looks exactly right. The logo matches, the name checks out, and everything feels familiar. But something’s off. And before you realize what it is, you’ve handed over your login, your credit card, or worse, your network credentials. The trick wasn’t in the layout or the content. It was in the letters.

You click a link. It takes you to a site that looks exactly right. The logo matches, the name checks out, and everything feels familiar. But something’s off. And before you realize what it is, you’ve handed over your login, your credit card, or worse, your network credentials. The trick wasn’t in the layout or the content. It was in the letters.

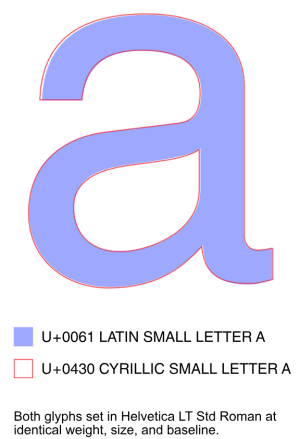

Cybercriminals are using homoglyphs—lookalike characters from other alphabets—to build fake domains that mimic real ones down to the pixel. A Cyrillic “а” is nearly identical to the Latin “a” your eyes expect to see. To a browser, they’re completely different. To a person, they’re the same. That’s the whole con.

This isn’t about sloppy typos or obvious fakes. There’s no misspelling, no swapped letters, nothing to trip up a cautious user. These attacks work because there’s nothing to spot unless you’re scanning for Unicode values instead of reading words. The danger is invisible. One legitimate domain can be spoofed in millions of ways using homoglyphs. And each one can lead to a phishing site that feels legitimate until the moment your credentials are gone.

A 19-character domain with just three visually similar alternatives per letter opens the door to billions of possible combinations. Even if only a handful of letters are swapped, attackers can generate thousands of convincing fakes. That scale makes it impossible to secure every variation. Attackers only need one to work.

Back in 2017, security researchers documented a phishing campaign targeting PayPal users with a domain that looked exactly like “paypal.com” but used Cyrillic characters. To most users, the fake was perfect. The login screen looked identical. The domain appeared clean. Everything seemed in place—until credentials started flowing to the wrong hands. It was one of the first major cases that proved homoglyph attacks weren’t theoretical. They were live.

These domains are cheap to buy, easy to register, and quick to deploy. A few bucks and a free SSL certificate is all it takes to stand up a fake site that can run for days or weeks before getting flagged—if it gets flagged at all. Some are hosted in jurisdictions where takedown requests go unanswered. Others pop up, harvest credentials, and vanish before security teams can catch them.

To the untrained eye, they’re indistinguishable. The difference is buried in how browsers read characters under the hood. It’s like using a forged signature with identical handwriting but slightly different ink—visually convincing, technically distinct. Unicode was designed to support global languages, not to stop cybercrime. That flexibility allows attackers to pull letters from Cyrillic, Greek, Armenian, and other scripts to mimic English words.

Browsers try to help, but the defenses are patchy. Some display punycode—the raw encoding that reveals when mixed alphabets are used—but only under certain rules. Many still show the fake domains as normal. On mobile devices, where fonts are smaller and screens are tighter, spotting a difference is even harder.

Traditional security tools aren’t built to catch this. Domain filters don’t block brand-new registrations. Email filters might not trigger if the message looks clean. Even AI-based systems can miss them because the code behind the site isn’t inherently malicious. It’s the context that makes it dangerous.

Homoglyph attacks aren’t just a technical risk. They’re a trust problem. A customer who falls for a fake login page doesn’t blame the scammer. They blame the brand. And when that happens, it’s not just about stolen credentials—it’s about reputational damage. The cost isn’t measured in passwords. It’s measured in lost confidence.

Some companies try to preempt the problem by registering common lookalike domains. Others invest in brand monitoring services that scan the internet for impersonators. These strategies help, but they don’t solve the core issue. You can’t buy up billions of variants. You can’t count on users to spot an invisible trick buried in plain text.

The web teaches people to trust what they recognize. Homoglyph attacks weaponize that instinct. The site looks right. The domain looks right. But one letter isn’t. And that’s all it takes.